In Honor of the Late Taewan Kang – Questions Amidst the Political Turmoil in South Korea

In Honor of the Late Taewan Kang – Questions Amidst the Political Turmoil in South Korea

In Honor of the Late Taewan Kang – Questions Amidst the Political Turmoil in South Korea

By: Subin Cho (M.A. Candidate of International Regional Studies, Seoul National University)

“Another 'Machinery Entrapment Death': Migrant Worker Dies at Special Vehicle Manufacturing Factory in Gimje”[1].

Let me begin by inviting you to reflect on a simple question: Who is a migrant? What do they look like? Where might they live, and what language might they speak?

The answer is straightforward: a migrant could be someone just like you. The photo below shows a migrant—me, the author. I appear Korean, I live in Geumcheon-gu, Seoul, and I speak Korean fluently. From this, you wouldn’t guess that I have spent most of my life living abroad.

Figure 1 Subin Cho

(Source: Courtesy of Subin Cho)

I have lived and studied in South Korea, China, and the United States (ten years in each region on average), and my first job as a fresh college graduate was in Tokyo, Japan. All of these stages reinforced my identification with the concept of migrant. Hence, I closely resonate with the migrant population in general, not to mention the ones in Korea, where I am from.

My academic interest in migrants further evolved when I returned to Korea in 2019, reconnecting with my heritage and re-examining my relationship with this place. This shift in perspective led me to become involved in migration study. It was epitomized by my encounter with the late Taewan (Taivan in Mongolian, hereafter Taewan) Kang, a 32-year-old “migrant” from Mongolia, who lived in Korea for 26 years under an undocumented status.

Taewan is a poignant example of the issues I wish to discuss in this piece regarding the migrants in Korea. Taewan lived in Korea for 26 years under an undocumented status. His tragic death in a workplace accident highlighted for me the deep inequities that migrant youth face in South Korea, particularly in terms of legal status, systemic exclusion, and the lack of social safety nets for migrant communities.

ㅤ

ㅤ

ㅤ

Figure 2 The Late Taewan Kang

In the midst of the recent political turmoil in South Korea, marked by the proclamation of Martial Law, I have deeply felt, as a citizen, the collective concern for the safety and well-being of this country and its “people”. However, the question I wish to pose is: Was Taewan not one of the “people” of South Korea?

I first encountered Taewan`s story through an obituary[3] written by Dr. Sagang Kim, an activist affiliated to MIHU (Migrant & Human Rights Institute). MIHU aims to be an “alternative research institute” that reads, writes, speaks, and learns to advocate for the human rights of minorities, including migrants. Its activities include investigating and revealing the realities faced by minorities; developing and proposing policies for social change; providing educational programs to engage broader audiences; strengthening the capacities of activists, and supporting and advocating for the rights of migrants who have experienced human rights violations.[4]

The earliest research of MIHU regarding the migrant issues in South Korea went back to the year of 2007. With more than 17 years of history, MIHU has been contributing to the issue of migrants in South Korea. Its most recent press conference titled as “WE ARE ALL DREAMERS,” is from a slogan devised by youth with migrant background in Korea. In the conference, MIHU with all other parties interested urged to create a space where all children and youth with migrant backgrounds could raise their voices and assert their undeniable right to stable residency.[5]

Now, back to Taewan`s story – despite the efforts to obtain legal residency and fully integrate into Korean society, systemic barriers such as legal uncertainty persisted throughout his life. Although he briefly returned to Mongolia under a government program, he managed to re-enter South Korea with a student visa and later pursued permanent residency.

However, Taewan`s path was fraught with challenges, culminating in his untimely death while working in unsafe conditions. Taewan's story exemplifies the systemic neglect and exploitation faced by migrants in South Korea, highlighting the urgent need for a society that ensures safety, dignity, and equitable opportunities for all, including migrants.

According to Dr. Sagang Kim, who supported Taewan for 18 years, Taewan was neither a "migrant worker" nor a "Mongolian" in the traditional sense. Taewan was a “migrant” who could only speak Korean and identified himself as a Gunpo saram, a native of Gunpo City.[6] His entire journey was marked by uncertainty and instability, and it was an immense challenge. However, Taewan quietly walked his path, determined to become a “citizen” of South Korea, a country that rejected him. Yet, South Korea and its safety negligence allowed Taewan, who had moved to Gimje City, to disappear within just eight months [7]

As Dr. Kim noted, the tragedy exemplified how the South Korean government views migrants—simply as tools for production, consumption, and taxation.[8] The death of a young undocumented migrant in Korea highlights systemic challenges. Taewan`s precarious legal status and lack of access to social safety nets mirror the barriers migrants face in Korean society.[9] The Korean government fails to consider whether the paths it pushes migrants to follow are sustainable for their lives. Instead, it exploits their hopes of settling in Korea, pushing them to live in unfamiliar places and work in more difficult and dangerous conditions.[10]

The bereaved and the company employed Taewan reached a settlement on Dec 10th, and from Dec 13th, the memorial service was organized for Taewan. Whilst I feel relieved about this news, I also had my concerns regarding how Taewan`s story would be accommodated by the Korean society, amidst the recent imposition of Martial Law.

Yes, we should not turn away from what is happening now in this country, as the issues of migrants and politics (policies) are inseparable from each other. The recent Martial Law occurred for the first time in 45 years in Korean history. As someone who identifies as both Korean citizen and a migrant, I felt both anger at the president for instilling fear of dictatorship among the public and deep concern for people in Korea.

While issues about minorities have always sparked various debates, in times like these, they are often dismissed under the guise of avoiding "dividing the nation,” as feminist activist Mi-seop Shim[11] aptly pointed out. I believe it is crucial for us to stand as strong allies to migrants in Korea, especially during these times. Citing the brilliant idea of Hyunkyung Kim, it is because while individual efforts may have limitations, our society, as a collective, has the capacity to address and support this cause effectively. [12]

I fully agree with Kim`s argument that the chasm between absolute hospitality and conditional hospitality is not an “unbridgeable divide,” but rather a result of confusing the openness of private spaces with the creation of public spaces.[13] I hope people do not turn a blind eye to issues that require our attention. The ubiquity of the suffering exists among certain groups, especially the one that could be categorized as minorities. [14]

I must clarify here that I do not subscribe to the absolute framing of all migrants living in South Korea as vulnerable individuals in need of help. However, if there are migrants among us who are suffering as part of our society, we, as members of the community, are obligated to collaborate with them. Whilst it is evident that there are migrants who were unable to pass with dignity even in emergencies due to language barriers and systematic exclusion even for now, we as a society must alleviate those suffering.[15].

How can South Koreans all live equally, alongside migrants? How can we “strive for a society where migrants do not have to engage in dangerous work to survive, where the workplaces migrants labor in are safe, and where the paths they choose are not dead-ends[16]?” First and foremost, we must remember how “we all arrived in this world as strangers, and it was through acts of hospitality that we were brought into society.”[17]

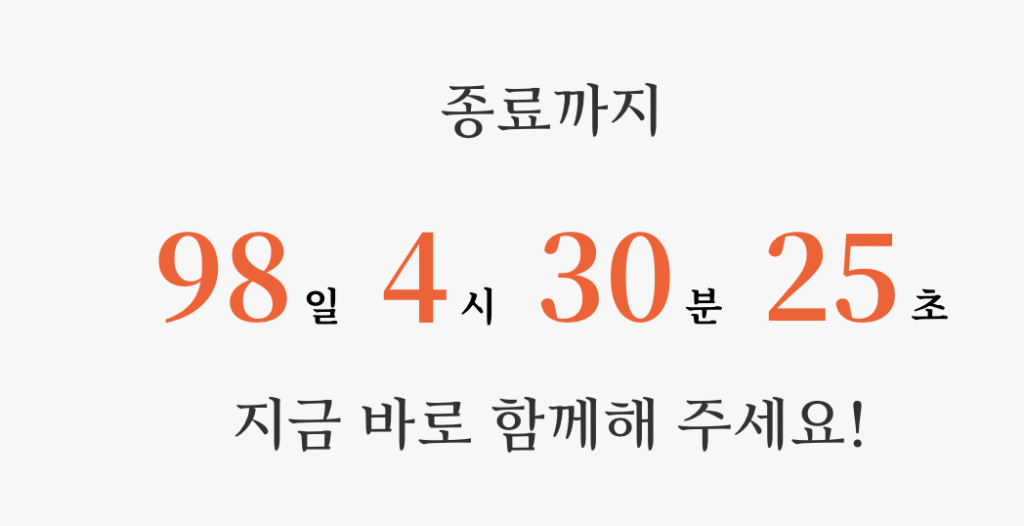

MIHU has launched the "LET US DREAM: Nurturing the Dreams of Migrant Children Here and Now[18]. " campaign, the activism in which Dr.Sagang Kim had prepared with Taewan. The LET US DREAM campaign aims to prevent the termination of the Ministry of Justice's relief measures for undocumented migrant children, which allowed Taewan to obtain residency status and a foreigner registration card after 25 years.

The campaign seeks to institutionalize these relief measures, ensuring that undocumented migrant children are granted stable residency status. Furthermore, it advocates for policies that provide all migrant children who have been educated and raised in Korea with the opportunity to pursue further education, employment, or even time to explore their career paths after graduating high school, supported by stable residency rights.[19] It is estimated that there are approximately 20,000 undocumented migrant children living in South Korea. Between April 2021 and August 2023, 962 undocumented migrant children were granted residency status and registered as foreign residents. This was made possible through the Ministry of Justice's relief measures for long-term undocumented migrant children. However, compared to the estimated 20,000 undocumented migrant children in the country, only a very small fraction has been granted relief. [20]

The Ministry of Justice’s relief measures for undocumented migrant children are set to end on March 31, 2025. After that date, undocumented migrant children who fail to apply for residency will lose the opportunity to continue living in South Korea. Is it not possible for these undocumented migrant children, who have been educated, grown up, and come to regard South Korea as their home, to remain here and dream of a future?[21]

We have 98 days left. last question to you is, the question I always have asked to myself and others – where is home for you? If you identify your home as Korea, how do you envision this place to be a safe place for all of us?

Figure 3

About the Writer

My name is Subin Cho, a M.A. Candidate in Seoul National University. Throughout my academic and personal journey, I have consistently sought to engage in activities that reflect my passion for social inclusion, cultural diversity, and global citizenship.

Since my matriculation to SNU GSIS from March 2022, I was privileged to be one of the founding members of Migration Study Group (“MSG” in short), supported by The Center for Transnational Migration and Social Inclusion (CTMS). I was able to initiate discussions on migration trends and policies with my distinguished peers and the researchers from CTMS. Last but not least, special thanks to everyone in CTMS and Dr.Sagang Kim of MIHU.

[1] Changhyo,Kim. “또 ‘기계 끼임 사망’···김제 특장차 제조공장서 이주노동자 숨져” (Another “Machinery Entrapment Death”: Migrant Worker Dies at Special Vehicle Manufacturing Factory in Gimje)The Kyunghyang Shinmun, Nov 2024, https://www.khan.co.kr/article/202411081550001

[2] Photo : “LET US DREAM: Nurturing the Dreams of Migrant Children Here and Now.” MIHU https://letusdream.campaignus.me/home#s202411019e7a66a7fed72

[3] Sagang, Kim. “부고 : 떠난 태완을 위해 다시 시작합니다 (Obituary – Starting anew for Taewan, who has left us) MIHU(Migration & Human Rights Institute), NOV 2024, https://stibee.com/api/v1.0/emails/share/dgT6K0CI2xxTIt4MzXX1IT0UY1ij8jg

[4] Introduction, MIHU. https://mihu.re.kr/introduction/

[5] MIHU. “장기체류 미등록 이주아동 체류권 보장을 위한 기자회견” (Press Conference to Advocate for Residency Rights of Long-Term Undocumented Migrant Children), NOV 2024, https://mihu.re.kr/activities/migrant-children-20241116/

[6] MIHU. “떠난 태완을 위해 다시 시작합니다”(We begin anew for Taewan, who has departed), NOV 2024, https://mihu.re.kr/activities/taivan-obituary-241111/

[7] Ibid.

[8] MIHU. “<추모성명> 불안한 이주의 길을 헤쳐 나갔던, 故 강태완님을 추모합니다.”( Honoring the Late Taewan Kang, Who Braved the Uncertain Path of Migration), NOV 2024, https://mihu.re.kr/activities/20241128/

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Mi-seop,Shim. “퇴진 집회 발언 : 페미당당 심미섭”(Speech at the Resignation Rally: Sim Mi-seop of Feminism Dangdang), DEC 2024, https://www.instagram.com/p/DDRdF3uTe9W/?img_index=1

[12] Hyunkyung, Kim(2016). “사람, 장소, 환대” (Human, Place, Hospitality). 문학과 지성사.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Hyunmi, Kim. Yonsei University “비판적 에코페미니즘 – 젠더 정의와 종간 정의의 모색” 강연 중, 서울대 여성연구소 (NOV 29, 2024)

[15] Nahyun,Kim.Solidarity with Migrants. “의사소통은 이주민의 기본권” 강연 중, 서울대 국제대학원 CTMS (DEC 06, 2024)

[16] MIHU. “<추모성명> 불안한 이주의 길을 헤쳐 나갔던, 故 강태완님을 추모합니다.”( Honoring the Late Taewan Kang, Who Braved the Uncertain Path of Migration), NOV 2024, https://mihu.re.kr/activities/20241128/

[17] Hyunkyung, Kim(2016). “사람, 장소, 환대” (Human, Place, Hospitality). 문학과 지성사.

[18] MIHU. “LET US DREAM: 이주배경 아동&청소년이 배우고 자라온 한국에서 계속 꿈을 키워나갈 수 있도록 캠페인에 함께 해주세요”(LET US DREAM: Nurturing the Dreams of Migrant Children Here and Now), https://letusdream.campaignus.me/home#s202411019e7a66a7fed72

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.