Gender ideology and fertility in South Korea

Gender ideology and fertility in South Korea

Gender ideology and fertility in South Korea

JaYung Moon (Master's Student at Yonsei University, Intern at the Center for Transnational Migration and Social Inclusion of Seoul National University)

The Republic of Korea (henceforth South Korea) has undergone an era of development since the 1960s, restructuring its socioeconomic structure after the Korean war. Average education levels expanded from less than primary education to tertiary education in just 60 years while a rapid shift between economic boom and uncertainty led to difficulties in employment (Hannum et al. 2019). Such transformation went along with the demographic restructuring of South Korea’s population, centered around individuals living longer yet no longer giving birth.

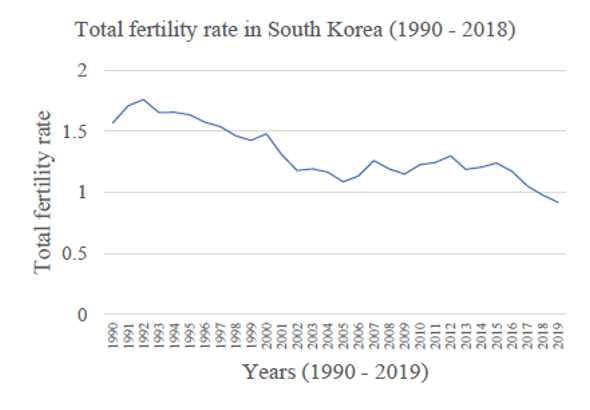

Decline in marriage, rise in divorce, and decrease in fertility is a pattern all post-industrial societies experienced during the second half of the 21st century, but many have recorded a recovery since the late 1990s. However, South Korea went aside as an exemption. The country’s fertility rate continuously decreased to historically low levels, recording lowest-low fertility rate of 1.3 since 2001 and dropping to 0.98 in 2018 (Arpino et al 2015; Lee and Choi 2015). As of 2020, South Korea is recording a first-ever natural population decline as death outpaced births in November (Statistics Korea).

Figure 1 – Total fertility rate trend of South Korea (1990 – 2018)

Fertility trends as such has never been recorded before, and many attempts to explain the cause behind such phenomena has been done. However, examining each countries’ socioeconomic status and patterns of gender revolution, recent research began to focus on gender ideology as the cause behind fertility rates. McDonald (2000)’s gender equity theory views that “very low fertility is the result of incoherence in the levels of gender equity in individually oriented social institutions and family-oriented social institutions”, indicating that perceived unfairness experienced between gender is the cause of such phenomena. Similarly, Esping- Andersen and Billari (2015) and Goldscheider et al. (2015) shares a point of view on looking into the difference in gender norms and fertility rates, pointing out that fertility rates have recorded a reversal trend in some countries where labor force participation of women and fertility rates have increased simultaneously.

Evaluating the types of gender ideology and the effect it has on birth, which is one of women’s most fundamental reasons to defer from the paid labor market, research diverged into the types of gender ideology, differing from the traditional perspective of viewing gender ideology on a single continuum. Using the General Social Survey data from 1977 to 2016, Scarborough et al. (2019) identifies six different gender ideology groups within the United States and indicate that the distribution of such gender ideology is slowly moving towards egalitarianism, but with increasing ambivalent views varying between the public and private sphere. Brinton and Lee (2016)’s results using latent class analysis also reveal the existence of multiple co-existing gender role ideologies across post-modern societies around the world and conclude that South Korea’s most dominant type of gender role ideology is “pro-work conservatism” which supports women’s roles as both a paid laborer but also as a primary caregiver. They also identified that along with South Korea, other countries with high percentage of “pro-work conservatism” such as Japan, Taiwan and Greece all turn out to be countries recording very-low fertility rates.

South Korea’s case

In the case of South Korea, women’s labor force participation is characterized by an M-shaped curve, with most women leaving the labor market due to marriage and birth. They rejoin when their child starts attending primary school but re-entering the labor force is more likely commenced amongst women without a second child (Kim 2014). Such patterns of career break indicate that birth and childcare is heavily dependent on women, and that division of labor between the labor market and household is skewed. Although recent cohorts record much less probabilities of experiencing career break after marriage, births are still a strong factor influencing the continuation of paid labor work (Eun 2018).

Research conducted amongst South Koreans on gender ideology and fertility correlate with existing statistics. Kim (2015) suggests that wives significantly contributing to household income are less likely to have a second child compared to those who contribute less, and Park (2008) provides evidence that men who participate in housework positively affect second child aspirations for working wives. Yoon (2016) reports that women’s gender ideology and husband’s participation in housework positively influences the likelihood of realizing the intentions of a second birth, while Yoon and Kim (2016) report that egalitarian women tend to refer seceding from the labor market than women with traditional gender ideology.

However, papers viewing gender ideology as multidimensional is yet rare in South Korea. Of the few, Chung et al. (2012) used clustering analysis revealing four different types of gender ideology. A point to notice is that the majority were classified as individuals with traditional views on filial responsibility, yet egalitarian towards gendered roles, which support that gender ideology on roles and responsibilities in the public and private sphere is multidimensional.

Keeping in mind that combining items into a unidimensional measure limits explanation on the different realms of the public and private sphere, follow-up research viewing gender ideology as multidimensional in South Korea is needed, as past research viewing gender ideology binarily may be diminishing the importance of the interplay between paid labor and unpaid labor (Scott 2010).

*This post has been re-organized from JaYung Moon’s master’s thesis.

References

Arpino, B., Esping-Andersen, G., & Pessin, L. (2015). How do changes in gender role attitudes towards female employment influence fertility? A macro-level analysis. European Sociological Review, 31(3), 370-382.

Brinton, M. C., & Lee, D. J. (2016). Gender-role ideology, labor market institutions, and post-industrial fertility. Population and Development Review, 405-433.

Chung, S.D, Bae, E.K, Choi, H. (2012). Patterns of supporting aged parents and gender roles: Generational comparisons. , 17(2), 5-23.

Esping‐Andersen, G., & Billari, F. C. (2015). Re‐theorizing family demographics. Population and development review, 41(1), 1-31.

Eun, K.S. (2018). Korean Women’s Labor Force Participation and Career Discontinuity. Korea Journal of Population Studies, 41(2), 117-150.

Goldscheider, F., Bernhardt, E., & Lappegård, T. (2015). The gender revolution: A framework for understanding changing family and demographic behavior. Population and Development Review, 41(2), 207-239.

Hannum, E., Ishida, H., Park, H., & Tam, T. (2019). Education in East Asian societies: Postwar expansion and the evolution of inequality. Annual Review of Sociology, 45, 625-647.

Kim, H. (2015). Women’s wages and fertility hazards in South Korea. Asian Women, 31, 1–27.

Kim, Y.M. (2014). Understanding family and labor coexisting policies on the intersectionality of gender and class. Journal of Social Science, 31(2), 1-26.

Lee, S., & Choi, H. (2015). Lowest-low fertility and policy responses in South Korea. In Low and Lower Fertility (pp. 107-123). Springer, Cham.

McDonald, P. (2000). Gender equity in theories of fertility transition. Population and development review, 26(3), 427-439.

Park, S. (2008). A study on the relationship of gender equity within family and second birth. Korean Journal of Population Studies, 31, 55–73.

Scarborough, W. J., Sin, R., & Risman, B. (2019). Attitudes and the stalled gender revolution: Egalitarianism, traditionalism, and ambivalence from 1977 through 2016. Gender & Society, 33(2), 173-200.

Scott, J. (2010). Quantitative methods and gender inequalities. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 13(3), 223-236.

Yoon, S. Y. (2016). Is gender inequality a barrier to realizing fertility intentions? Fertility aspirations and realizations in South Korea. Asian Population Studies, 12(2), 203-219.