Amidst Gender Gaps in South Korea’s Labor Market: The Motherhood Trap

Amidst Gender Gaps in South Korea’s Labor Market: The Motherhood Trap

Editorial | Amidst Gender Gaps in South Korea’s Labor Market: The Motherhood Trap

By: Minji Kang (Researcher Consultant)

In recent research, the Peterson International Institute of Economics (PIIE) examined individual-level data from the Korean Labor and Income Panel Study (KLIPS) for the years 2000 –19 to test the possibility of family and child considerations playing any substantial roles in explaining gender labor market gaps in South Korea.

One of the most interesting findings relates to the country’s employment gap, where motherhood seems to account for almost all of South Korea’s gender employment gap[1]. While unmarried women without children are just as likely as men to be employed, when estimating the effect of having a first child on women and men’s labor market outcomes, the study found that a large proportion of women leave the workforce when they have children. (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Regression-adjusted gender employment gap for women with and without children

Note. From “Why Gender Disparities Persist in South Korea’s Labor Market.” Figure 22, page 27, by Karen Dynan, Jacob Funk Kirkegaard, and Anna Stansbury, 2022, Washington DC: Peterson International Institute of Economics.

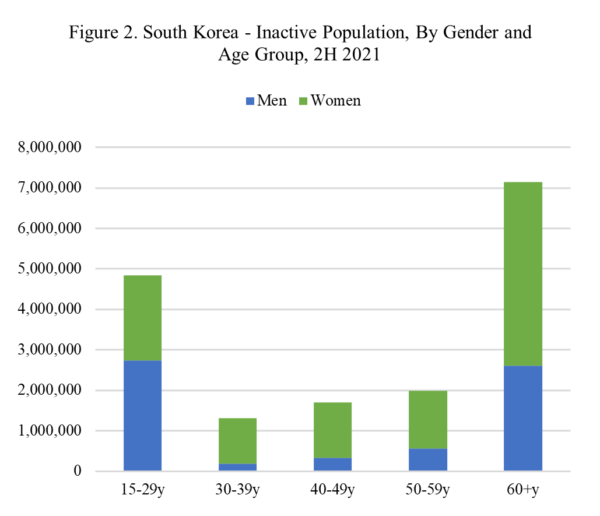

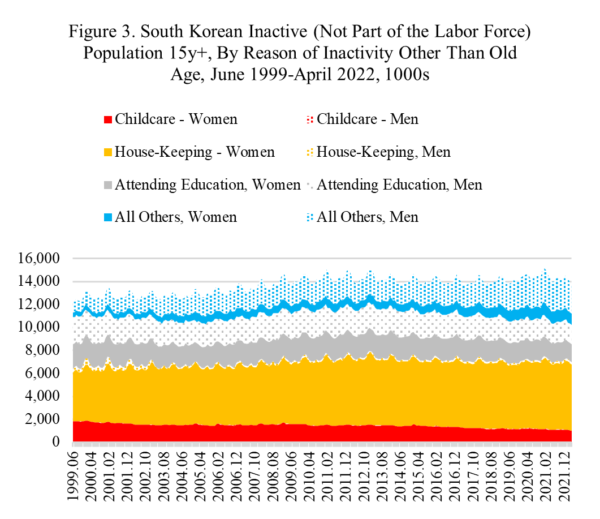

The data also showed that inactivity rates of prime-age[2] female workers are far above those of men in South Korea (Figure 2), with most inactive women, not retired nor enrolled in the educational system, engaged in childcare and/or housekeeping (Figure 3).

Note. From “Why Gender Disparities Persist in South Korea’s Labor Market.” Figures and 6, page 7, by Karen Dynan, Jacob Funk Kirkegaard, and Anna Stansbury, 2022, Washington DC: Peterson International Institute of Economics.

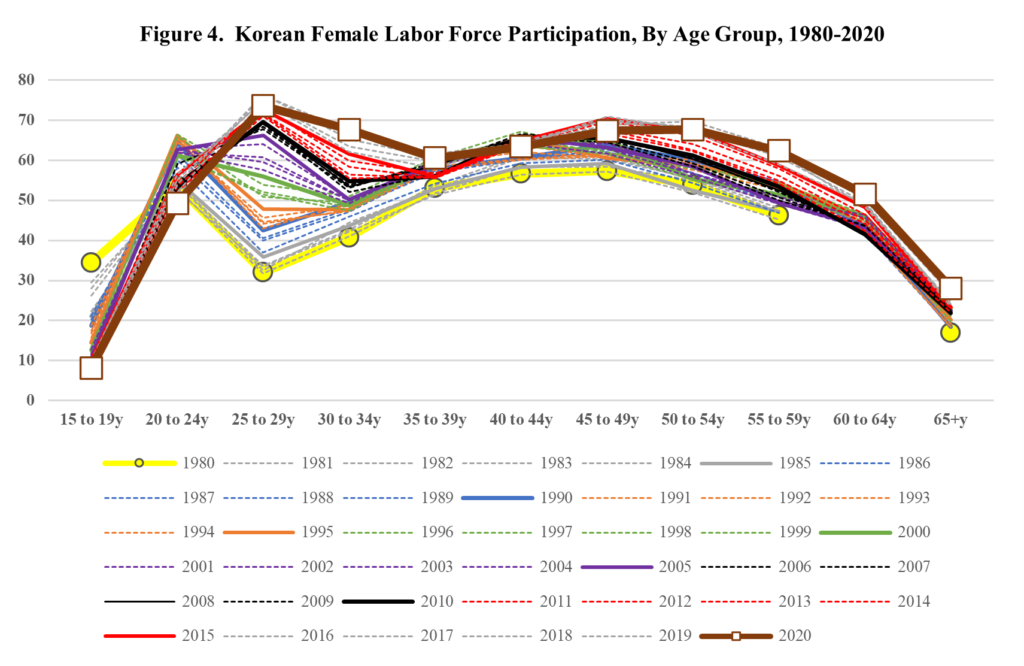

This is backed by an M-shaped behavior, with labor participation high at a young age, dropping during prime age (presumably due to family responsibilities), and then picking up again at older ages. Figure 4 reflects this trend and its changes throughout the years. While in 1980 Korean female labor force participation decreased during the ages of 20 – 29 and increased again after they turned 30 years old, today, female labor force participation in South Korea peaks in their late 20, falls in their 30s, and then rises again from age 40 to the early 50s. The 2020 drop occurs roughly 10 years later in the lifecycle than it did in 1980, as South Korean women now tend to stay in full-time education for longer before entering the labor force and have children at later ages. The average age of mothers giving birth to a child was 33.1 years in 2020[3].

Note. From “Why Gender Disparities Persist in South Korea’s Labor Market.” Figure 7, page 8, by Karen Dynan, Jacob Funk Kirkegaard, and Anna Stansbury, 2022, Washington DC: Peterson International Institute of Economics.

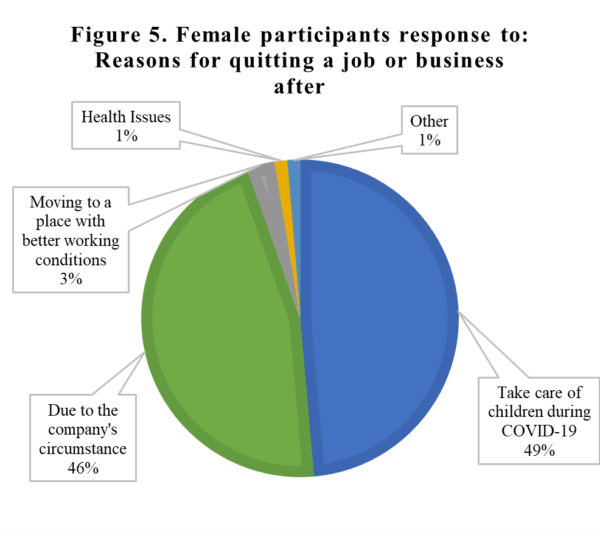

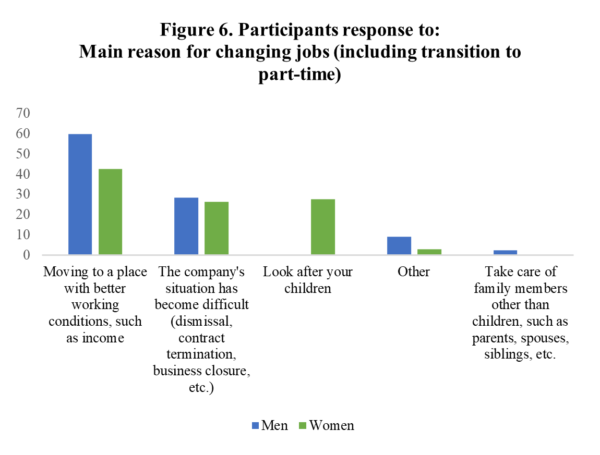

In line of these results, the Center for Transnational Migration and Social Inclusion’s (CTMS) findings point to consistent trends to the ones above, even during the COVID-19 pandemic. A survey conducted by CTMS found that during this crisis, around 49 percent of interviewed women listed taking care of their children as the number one reason they quit their jobs during this time (Figure 5), while 28 percent of women changed their jobs or shifted to part-time employment for the same reason (Figure 6)[4].

Source: Self-construction. CTMS, Gallup Korea. (2021) COVID-19 and Korea’s Childcare Survey

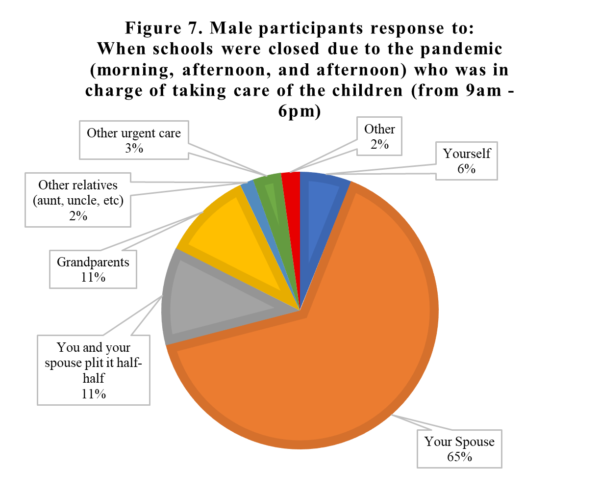

Care activities weigh heavily on Korean women as they are pressured to adhere to traditional gender roles where women oversee household matters. The very limited contribution of South Korean men to childrearing duties relative to those of their spouses adds to the deterioration of a woman’s employability as care responsibilities are placed on women[5].

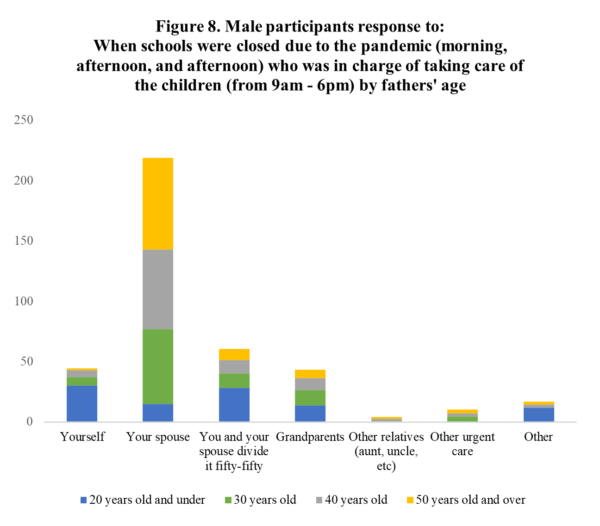

When asked who was in charge of childcare during the time when childcare institutions were closed due to COVID-19, i.e., from 9 am to 6 pm, 65 percent of interviewed fathers pointed to their spouses as the main care taker; 11.4 percent split the duties with their spouse while 6 percent were the main care takers themselves (Figure 7). Age indicates that older fathers have greater expectations of their spouses being the main childcare providers than younger fathers. Consistent to this, younger fathers are more prone to split childcare responsibilities half-half with their spouses (Figure 8).

Source: Self-construction. CTMS, Gallup Korea. (2021) COVID-19 and Korea’s Childcare Survey

This line of thought could suggest that the size of the “child earnings penalty” and its concentration on the extensive margin (employability of women, rigidities in the Korean labor market, etc.) mean that the cost of having a child in terms of forgone labor market access and/or opportunities is unusually high. Women are “pushed out” from the labor field for having children, thus disincentivizing them from remaining as active participants.

In terms of legislation, Korea already has a good basis for parental leave; however, the use of parental leave is limited, suggesting that better enforcement of access to these benefits is needed. Kim, Hwang, and Kim present substantial evidence that South Korean women, particularly those in nonregular jobs, working long hours, or not belonging to a labor union, are frequently unaware that they are eligible for maternity or parental leave or are concerned about the professional ramifications of taking it[6]. Even in the midst of a global crisis, CTMS’ survey found that only 31 percent of Korean parents used their annual paid leave to care for their children during times of school and day care center closures[7].

These considerations argue for policies that can shift the norms on parental caregiving for children. Such measures would increase gender equity, making more efficient the use of women’s talents in the workforce and helping to increase the reinstatement of mothers in the workforce. Most importantly, the country should incentivize flexibility in the nature of work, focusing on offering quality part-time jobs that allow parents to care for their children while retaining job value instead of temporary jobs, to ensure financial and employment stability. At the same time, safeguard coverage in the nonregular sector must be improved to allow parents on the peripheral side of the labor market have equal access to benefits and opportunities as they rejoin the labor force participation.

[1] Karen Dynan, Jacob Funk Kirkegaard, and Anna Stansbury (2022.07) “Why Gender Disparities Persist in South Korea’s Labor Market.” Working Paper 22-11. https://www.piie.com/publications/working-papers/why-gender-disparities-persist-south-koreas-labor-market\

[2] Prime working age refers to labor-force participation rate for women aged 25 to 54

[3] Statistics Korea. Birth Statistics in 2020 Report.

[4] CTMS, Gallup Korea. (2021) COVID-19 and Korea’s Childcare Survey. Seoul.

[5] Justin McCurry. (2021) Luxuries I can’t afford’: why fewer women in South Korea are having children. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jan/15/luxuries-i-cant-afford-why-fewer-women-in-south-korea-are-having-children

[6] Kim, E.J., W.J. Hwang, and M.J. Kim. 2021. Determinants of Perceived Accessibility of Maternity Leave and Childcare Leave in South Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 19: 0286. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8507878/.

[7] CTMS, Gallup Korea. (2021) COVID-19 and Korea’s Childcare Survey. Table 13-1-2. CTMS. https://ctms.or.kr/resources/publications?mod=document&pageid=1&uid=164